Cassius Marcellus Clay was born in 1810, the son of the weal…

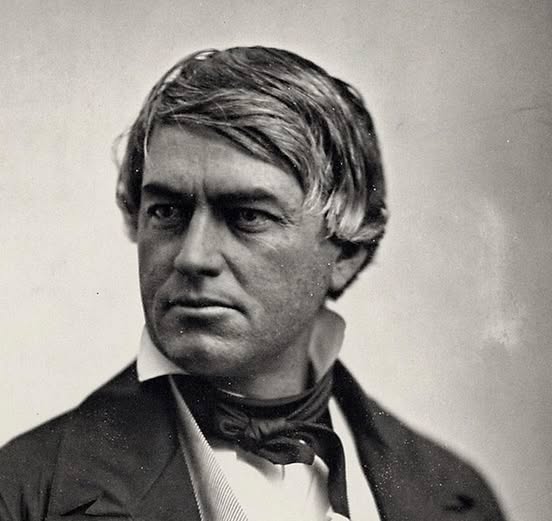

Cassius Marcellus Clay was born in 1810, the son of the wealthiest plantation owner in Kentucky. Upon inheriting his estate, he immediately freed all his slaves and even gave them a portion of his property. By his twenties, he had already served three terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives. But because of his outspoken opposition to slavery, he found it increasingly difficult to win elections in the deeply pro-slavery state. Instead of running again, he began traveling the country, delivering passionate speeches against slavery. He famously ended these speeches by placing a Bible on the podium and saying, “To those who follow God's law, I offer this book as the answer to slavery.” Then he would place a copy of the U.S. Constitution next to it and say, “To those who follow man’s law, I offer this book.” Finally, he would draw two pistols and lay them on the podium, declaring, “To those who follow neither, I offer this.” In effect, he was openly provoking slaveholders wherever he went. As expected, duel challenges followed. He accepted them all—and won. He killed several pro-slavery opponents. Clay’s favorite weapon was the Bowie knife, a heavy combat blade. He survived multiple assassination attempts; not only did he live through gunfire, he often retaliated immediately, killing his attackers with the knife. This violent readiness remained a part of him until he died of natural causes at age 92. But his life was not just defined by violence. A close friend of Abraham Lincoln, Clay was once considered for the vice presidency. However, due to his controversial and bloody reputation, Lincoln instead appointed him U.S. Minister to Russia. While serving in St. Petersburg, the American Civil War broke out. Though frustrated that he couldn’t fight in the war himself, Clay played a critical role in diplomacy: he helped secure the Russian Empire’s strong public support for the Union cause. Russia, at the time one of the few major powers backing the North, sent fleets to American ports as a show of force, implicitly warning Britain and France—who were considering recognizing the Confederacy—that any intervention would risk a broader war. Clay’s diplomatic efforts were instrumental in maintaining this alignment, which significantly weakened the South’s chances of gaining international legitimacy. Later, he also helped pave the way for the U.S. purchase of Alaska from Russia. In 1861, as the Civil War began, Lincoln wanted to bring Clay back from Russia and offered him a major general’s commission. But Clay refused, saying he would not serve unless all Southern slaves were freed. This stance helped pressure Lincoln into issuing the Emancipation Proclamation much earlier than originally planned. These were the brightest moments of Clay’s life—he had achieved his lifelong mission of abolition. The next four decades, however, were marked by erratic behavior and conflict. Still a troublemaker, but now without a cause, he became more of a public nuisance than a hero. He died in 1903 at the age of 92. His cousin, Henry Clay, had been one of the most prominent American politicians of his time and a leading presidential contender. The enslaved people owned by Henry Clay took on the surname “Clay.” One of their descendants, Herman Heaton Clay, named his son (born in 1912) Cassius Marcellus Clay and later his grandson (born in 1942) Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. in honor of the great abolitionist. That grandson would go on to become one of the most iconic athletes in history: after converting to Islam, he changed his name to Muhammad Ali and became the heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

Leave a Reply